INTRODUCTION

Ageing results in various changes in different aspects of life, including its social, mental and physical areas. An increasing number of older people are concerned about the challenges associated with ageing, and its effect on quality of life and independent functioning. One common fear is the onset of age-related cognitive decline1.

Cognitive functions are crucial for maintaining independence in daily life. While minor and subtle problems with cognition often manifest with age, some cases may be more pronounced than what would typically be expected for a healthy person of the same age; such cases are known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI)2. Impairments associated with MCI may lead to difficulties in daily tasks, financial management, adherence to health routines, and emotional stability3.

One crucial aspect of cognitive function which may deteriorate with ageing is the ability to hold and manipulate information temporarily. This skill is vital for understanding anything that unfolds over time, as it requires considering past events and relating them to future ones. As a result, it plays a key role in comprehending written and spoken language, performing calculations, organizing thoughts, evaluating alternatives, and integrating new information into existing plans or updating them4. However, it is notably impaired in individuals with MCI. Research suggests that deficits in this area can predict a decline in daily functioning and the progression to more severe cognitive disorders within a year5.

Given that cognitive decline is a progressive process with no definitive cure, numerous studies have developed programs to enhance cognitive functions in MCI. Their findings highlight the crucial role played by of rehabilitation medicine specialists in managing the condition through targeted cognitive interventions6. These interventions can be categorized into physical, diet, lifestyle, socialization and cognitive approaches7. The choice of cognitive intervention is influenced by several key parameters, which require careful consideration by specialists. Research has highlighted the importance of working memory (WM), the ability to manipulate and update information, as a critical component in cognitive intervention8.

As WM plays a critical role in MCI, it has been used as the target of a variety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions and programs aimed at improving cognitive function. Two key non-pharmacological approaches are brain stimulation and cognitive interventions (CIs). While previous meta-analyses have explored brain stimulation and its various types9, CIs encompass a range of aspects examined in previous studies.

A systematic review of the impact of computerized cognitive training on MCI concluded that current evidence does not definitively support its efficacy in improving MCI symptoms10. Similarly, another systematic review assessed the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation (CR) and physical exercise, finding that both simultaneous and sequential combined interventions are effective in promoting cognition11. A meta-analysis by Hu et al.12 examined the efficacy of computerized cognitive rehabilitation at two stages: subjective cognitive decline and MCI; the findings indicate that computerized cognitive rehabilitation is particularly effective in the subdomain of memory12. A meta-analysis by Wang et al.13 considered various non-pharmacological interventions, including physical exercise, brain stimulation, cognitive training, cognitive rehabilitation, musical therapy, and multi-domain interventions; the analysis showed that all these approaches, except for cognitive rehabilitation, can be effective in improving cognition in patients with MCI13. Another meta-analysis found the combined effects of exercise and cognitive training to improve WM in individuals with MCI, but further research is needed to fully understand its effectiveness compared to single interventions14.

While various review studies have examined different aspects of CI on cognitive function, none have specifically concerned WM. Therefore, the present study is the first such meta-analysis to specifically focus on improving WM in MCI, given its importance as a core component of cognitive function in MCI patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search of PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Science Direct was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines15 with the final conducted on March, 2024. The search keywords included: Mild Cognitive Impairment, Working Memory, Training, Rehabilitation, and Intervention. Google Scholar and the Scientific Information Database (SID) were also searched for articles in Persian; this search used equivalent keywords in Persian. The search terms were applied to both titles and abstracts using Boolean operators. The search was limited to human studies, and no language restrictions were applied except for Persian and English.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria based on the PICOS framework16. Population (P): Studies that recruited participants diagnosed with MCI according to standardized criteria such as DSM-IV or DSM-5-TR. Intervention (I): Any non-device and non-pharmacological cognitive interventions. Comparison (C): Studies that included either a control group receiving no intervention or an active control group. Outcomes (O): Studies investigating mental status outcomes (e.g., MOCA and/or MMSE) as primary outcomes, and cognitive measures (e.g., executive function, cognitive flexibility, attentional bias) as secondary outcomes. Study Design (S): Studies employing either a parallel (between-subject) or crossover (within-subject) randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. Additionally, for inclusion in the meta-analysis, studies had to use the backward digit span test for WM assessment and include a control group.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1) Significant cognitive impairment, Parkinson’s disease, or conditions where cognitive impairment is secondary to another factor such as hypothyroidism, use of zolpidem, sleep disorders, head injury, or stroke; 2) Interventions involving brain stimulation devices, neurofeedback, virtual reality, or medication; 3) Case studies, cross-sectional studies, literature reviews, meta-analyses, conference presentations, or case reports.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened to determine eligibility for full-text review, after which the full text of the selected studies was reviewed. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and in consultation with the senior authors (Z.S. and R.B.).

Data extraction

For the included studies, author information, group characteristics (intervention and control, sample size, mean age), baseline mental status parameters (e.g., MOCA and/or MMSE scores), cognitive measures and instruments (e.g., Digit Span), assessment duration (pre-post-follow-up), and the results of cognitive assessments were extracted from the full texts of the studies.

Risk of bias

The quality of the included studies in the meta-analysis was assessed using the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool (RoB-2). Studies with a high risk of bias were excluded if two or more domains were flagged as high risk or if the overall ROB was high17.

Data analysis

After obtaining the checklist for the review of articles, studies that met the criteria for meta-analysis were examined. Articles that did not report the mean and standard deviation, did not have a control group, or did not use the “backward digit span test” for assessing working memory were excluded from the meta-analysis. Each selected study, with an intervention group and a control group, were compared based on standardized mean difference (SMD; Hedge’s g) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed). The I² statistic was used to estimate between-trial heterogeneity, with values of ≤ 40% considered low heterogeneity, 40–60% moderate heterogeneity, and > 60% high heterogeneity18. Meta-analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (CMA) version 2.

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by repeating the meta-analysis using alternative assumptions to assess the influence of potentially arbitrary decisions and to detect any outlier effect sizes; the analysis was repeated after each alteration. Potential outlier studies or publication bias were detected using a funnel plot. In a funnel plot, each study’s weight, sample size, or inverse variance is plotted against the treatment effect size. An inverted funnel shape indicates no publication bias, while an asymmetric funnel plot may suggest the presence of publication bias19-20.

Synthesis Methods

To evaluate the efficacy of non-pharmacological cognitive interventions on WM in MCI, the results were synthesised using a random and fixed-effects meta-analysis. The analysis included studies meeting the meta-analysis criteria based on the PICOS framework. The comparability of the eligible studies was evaluated by summarizing the characteristics of the interventions, sample sizes, and primary and secondary outcome measures, ensuring alignment with the established eligibility criteria. The Standardized Mean Difference (SMD; Hedge’s g) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to determine the effect size for each selected study, comparing the intervention group to the control group (p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed). Statistical heterogeneity between trials was estimated using the I² statistic. Results from individual studies were visually displayed using forest plots, summarizing effect sizes and confidence intervals. Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the robustness of findings by excluding studies with a high risk of bias.

RESULTS

Search results

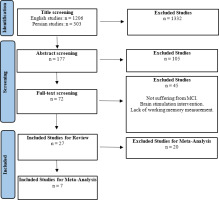

Following the initial database search, a total of 1509 articles were identified (303 in Persian and 1206 in English). Of these, 1332 articles were excluded based on their titles. Next, 177 articles were reviewed based on their abstracts. After removing 105 articles, 72 remained for full-text assessment. Of these 72 articles, 45 were excluded due to criteria such as MCI, brain stimulation interventions, or lack of WM measurement. Thus, 27 articles were reviewed in detail, and seven were found to be eligible for meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

The distributions of the age, number of participants, and cognitive impairment scale scores for both the intervention and control groups in the studies are given in Table 1. In total, 23 English-language studies (approximately 85%) and four Persian-language studies (approximately 14%) were included. Only two studies included control groups comprising healthy older adults (approximately 7%; 21-22). Lee and colleagues23 had the highest number of participants, i.e. 116 individuals in the treatment group and 113 in the control group. In contrast, the smallest study was conducted by Zare and colleagues24, with six participants in each group.

Table 1

Sample characteristics

Intervention Modalities

The review examined various types of interventions. Some studies included multiple types of interventions simultaneously. The type of intervention used in the studies, according to reference number, can be observed in Table 2.

Table 2

Classification of studies by intervention type

This review identified five distinct interventions. “Cognitive intervention” was categorized into three parts: digital-based training, involving tablets, mobile devices, and computer-based sessions; group-based training, involving cognitive rehabilitation or training in a group setting with paper and pencil features; and teaching strategies, which encompassed classes where participants were educated in various cognitive ability domains. “Exercise interventions” included structured physical activation with a coach. “Mindfulness-based interventions” comprised sessions focused on cultivating mindfulness. “Socializing interventions” involved social interactions for participants in different situations, and “dietary regimens” included specialized regimens intended to induce changes in cognitive functions. Ultimately, the most commonly-utilized intervention was digital-based cognitive activation, with mindfulness being observed in just one study.

The studies involving digital-based cognitive interventions used various types of software, mobile apps, and online programs. These included the Cogniplus25, the Brave mobile app23, the Lumosity mobile app26, INSIGHT online program28, CogMod30, CogMed31, NeuronUp32, and Happyneuron33.

Additionally, some studies programmed their training exercises in Java34, Android35, and E-prime27. Five studies implemented “group-based interventions”. Two studies22-37 focused on cognitive training sessions where participants exercised specific cognitive skills. One study36 involved a writing training program, specifically in calligraphy. Another38 incorporated various activities, including singing, playing, and engaging in art and craft. A third26 included pottery, painting, cooking, tap-dancing, playing brass instruments, rope craft, genealogy, British sign language, digital photography and drawing.

“Teaching strategies” included stress and mood management, coping with memory deficits in real life37-40, and metacognitive training39. Regarding “social activities”, one study23explored the implementation of a communication strategy, while another38 involved visiting cafes, shopping, and participating in events.

Intervention Duration and Follow-Up Assessment

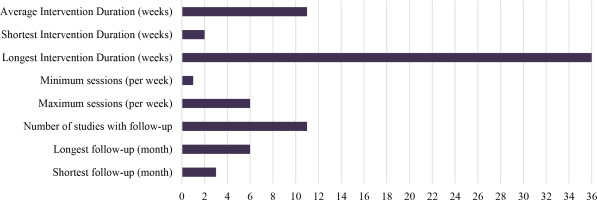

The mean duration of interventions was approximately eleven weeks. The longest intervention period was thirty-six weeks46, while the shortest was only two weeks22. The maximum number of sessions per week was six sessions43, and the minimum number of sessions was one per month46. Eleven studies (approximately 40%) included follow-up assessment. The longest follow-up duration was six months34-36-39. The shortest follow-up duration was three months23-25-29-30-35-40.

One study was quite unusual in that the pre-test was conducted two weeks before the start of the intervention36, with the post-test occurring two weeks after completion, and a follow-up assessment two weeks after a six-month interval from the post-test. Another study26 used one group as both the treatment group and control group: after the pre-test, all participants were maintained in the control phase for four weeks, after which the first post-test was conducted, followed by the initiation of the intervention phase. After thirty-two weeks of intervention, the second post-test was administered. The remaining studies met the pre-test and post-test conditions (Figure 2).

Primary and secondary outcomes

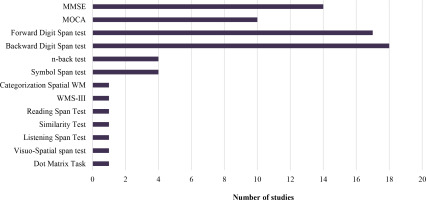

Of the included studies, 48% used the MMSE test, 33% employed the MOCA test, 14% did not report the scale used, and one study (5%) utilized both. Various tools were used to assess WM, with the Forward Digit Span test (63%) and Backward Digit Span test (66%) being the most common. The Symbol Span and n-back tests were each used in 15% of cases. Other assessments included CWMS, Dot Matrix Task, Visuo-Spatial Span Test, Listening Span Test, Similarity Test, and Daneman-Carpenter Reading Span Test. Only one study fully utilized the Wechsler Memory Scale, Third Edition (Figure 3).

Of the studies reviewed, six (22%) reported no significant differences in WM based on the measurement tools used in the intervention. The remaining studies showed significant improvements, no significant improvements, or a combination of both. Among the studies with follow-up assessments, two (18%) found no significant differences in WM, while the others showed a mix of significant and non-significant results. The summary from the reviewed studies presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Summary of reviewed studies

| Study number | Author | Intervention | Instrument | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Azhdar et al. 44 | EI | N-back | Pre-Post |

| 2 | Bae et al. 38 | EI+CT+SI | SST/ VSST | Pre-Post |

| 3 | Carretti et al. 22 | CT | FDS/ BDS/ CWMS/ DMT | Pre-Post |

| 4 | Chan et al. 36 | Writing | BDS | Pre-Post-6 month Follow up |

| 5 | Chobe et al. 43 | Yoga+AR | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post |

| 6 | Damirchi et al. 35 | EI+ ME | FDS | Pre-Post-3 month Follow up |

| 7 | Dannhauser et al. 26 | EI+CT+SI | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post(1)-post(2) |

| 8 | Donnezan et al. 33 | CT+EI | FDS | Pre-Post |

| 9 | Dossantos et al. 42 | RT | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post |

| 10 | Emsaki et al. 40 | MEST | WMS-III | Pre-Post-3 month Follow up |

| 11 | Fin & McDonald 27 | CT | SST | Pre-Post |

| 12 | Flak et al. 31 | CT | SST | Pre-Post-4 month Follow up |

| 13 | Gharabaghi et al. 45 | EI | n-back | Pre-Post |

| 14 | Giuli et al. 37 | CT | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post |

| 15 | Gonzalez et al. 32 | CT | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post |

| 16 | Herrera et al. 34 | CT | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post-6 month Follow up |

| 17 | Li et al. 23 | EI | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post-3 month Follow up |

| 18 | Lin et al. 28 | VSOP | N-back | Pre-Post |

| 19 | Moro et al. 39 | Metacognition | LST | Pre-Post-6 month Follow up |

| 20 | Schaham et al. 21 | TECH | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post |

| 21 | Vermeij et al. 30 | CT | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post-3 month Follow up |

| 22 | Weng et al. 29 | CT | FDS/ BDS/ DST/ ST | Pre-Post-3 month Follow up |

| 23 | Yang et al. 25 | VIMT | BDS | Pre-Post-3 month Follow up |

| 24 | Yoon et al. 41 | EI | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post |

| 25 | You et al. 47 | CCS | FDS/ BDS/ n-back | Pre-Post |

| 26 | Yu et al. 46 | MBI | FDS/ BDS | Pre-Post |

| 27 | Zare et al. 24 | CT | RST | Pre-Post |

[i] AR- Ayurveda Rasayana, CCS- Cosmos caudatus supplement, CT- Cognitive training, CWMS- Categorization spatial working memory, DMT- Dot matrix task, DR- Dietary regimen, DST- Digit symbol test, EI- Exercise intervention, LST- Listening span test, MCFT- Multi-domain cognitive function training, MBI- Mindfulness-based intervention, ME- Mental exercises, MEST- Memory Specificity Training, RT- Resistance training, RST- Reading span test, SI- Socializing intervention, SST- Symbol Span test, ST- Similarity test, TECH- Tablet Enhancement of Cognition and Health, VIMT- Virtual interactive working memory training, VSOP- Vision-based speed-of-processing, VSST- Visuo-Spatial Span Test, WMS-III- The Wechsler Memory Scale, Third Edition

Meta-Analysis Results

To allow consistent assessment and comparison of the post-test scores between the experimental and control groups, only seven of the 27 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

As revealed by the systematic review, certain studies utilized various assessments to evaluate WM. In such instances, our analysis focussed specifically on the data from the backward digit spantest. Nine studies in total employed the backward digit span. However, the some studies21-42 were excluded from the meta-analysis because they did not provide mean scores for the backward digit span test. Ultimately, seven studies were included in the meta-analysis, based on the post-test scores comparing the intervention and control groups.

Homogeneity

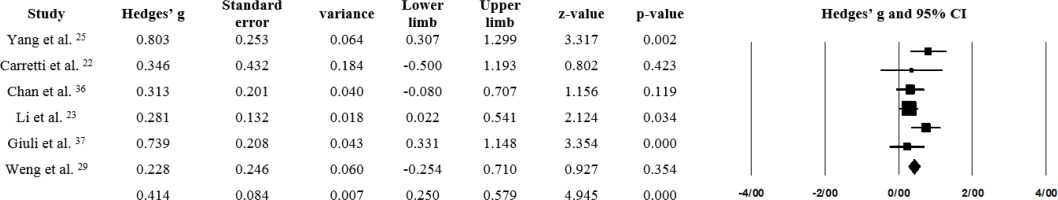

The homogeneity of the included studies was determined and their effect sizes are given in Table 4.

Table 4

Mean differences and effect sizes determined for the studies

| Study | Mean difference | Effect size |

|---|---|---|

| Carretti et al. 22 | 0.40 | 0.34 |

| Chan et al. 36 | 0.30 | 0.31 |

| Giuli et al. 37 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| Herrera et al. 34 | 0.36 | 1.77 |

| Li et al. 23 | 0.38 | 0.28 |

| Weng et al. 29 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| Yang et al. 25 | 2.09 | 0.8 |

TAs indicated by Table 4, the effect size of the study by Herrera et al.34 appears to contribute to an asymmetric distribution in the funnel plot. To further investigate this issue, we performed a sensitivity analysis. As seen in the plot on the left, the asymmetry in the diagram is derived from the effect size of one study.

After removing outlier effect sizes, the analysis was repeated, and the funnel plot appeared symmetrical, indicating homogeneity. The Q-value for the six studies was 6.68 (p = 0.247), suggesting no significant heterogeneity. Additionally, the I-squared value of 35% indicates low to moderate heterogeneity according to the Higgins criterion19.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias (ROB) assessment found the overall quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis to not be low. Three studies were classified as having “some concern” regarding risk of bias, while three were rated as having a “low risk”. Therefore, none of the studies were excluded from the meta-analysis based on the ROB measurement.

Effect Sizes and Forest Plot

The effect size was found to be 0.432 for the fixed-effects model and 0.456 for the random-effects model, with both values being statistically significant (p < 0.05; Table 5). Based on Cohen’s classification, these effect sizes fall within the medium range. The forest plot of the meta-analysis is presented in Figure 4. It was found that Li et al.23 holds the highest weight, while Yang et al.25 has the largest effect size.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of various cognitive interventions in enhancing working memory (WM) among older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The study is divided into two parts. The first part consisted of a systematic review of 27 studies, of which 16 reported significant improvements in working memory following cognitive interventions, seven found no significant effects, and four reported mixed results. Seven studies were then included in the second part, a meta-analysis based on similar assessments. The results of the effect size analysis indicated a medium effect size, suggesting that cognitive interventions have a moderateimpact on enhancing working memory in individuals with MCI. However, due to the limited number of studies included in our analysis, and the fact that we only considered the backward digit span as the most frequent and valid test for assessing working memory, our findings should be interpreted with caution. It is also important to note that the studies employed a variety of the cognitive interventions; nevertheless, for the purpose of the study, all were classified as non-pharmacological approaches.

Regarding the intervention modalities, our review takes a broader perspective than previous systematic reviews by also considering various types of cognitive interventions, as non-pharmacological approaches. It adopts a more holistic view of non-pharmacological interventions, recognizing their potential to complement pharmacological treatments or be used independently.

The most commonly-used approach in the analysed studies was computerized cognitive intervention (CCI). A previous review focusing specifically on the role of CCI in working memory among individuals with MCI demonstrated that CCI can lead to small to moderate improvements in WM in this population48. A key advantage of this non-pharmacological intervention is its ability to deliver personalized interventions, tailoring activities to meet the unique needs and abilities of each user25. Additionally, CCI has the potential to enhance self-efficacy by increasing motivation and reducing the fear of failure. This is achieved through the use of adaptive difficulty levels and personalized task allocations tailored to the individual’s abilities12.

Other commonly-used intervention modalities included physical activities and dietary regimens. Advances in neuroimaging have deepened our understanding of the roles these non-pharmacological interventions play in improving cognition. Physical activities have been shown to improve the functional aspects of higher-order brain regions involved in WM, while certain dietary factors appear to share similar mechanisms or complement the effects of exercise49. Molecular events, such as the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis, and increased synaptic plasticity, further contribute to the cognitive benefits of physical activities50-51. It has been suggested that physical and cognitive activities may impact brain plasticity through distinct yet complementary pathways. Given the transient release of neurotrophic factors following exercise, it is recommended that physical and cognitive activities be conducted in close temporal proximity to maximize their benefits, potentially with an order effect11.

Considerable variability in the intervention duration and follow-up assessments was noted between studies. For example, one study46 involved a 36-week Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI), while another22 lasted only two weeks, involving cognitive training targeting verbal abilities, working memory, flexibility, naming and movement. The results indicated that MBI did not lead to improvements in working memory, whereas cognitive training produced changes in spatial WM. This suggests that the type of modality used in the intervention may be more important for improving WM than the duration of the intervention. This idea is supported by Kardys et al.52, who found the modality of an intervention to influence the degree of enhancement in cognitive abilities. Additionally, Sanders et al.53 found that increasing the duration of intervention does not predict greater improvements in older adults with MCI. Furthermore, our present data indicates that the use of fewer sessions per month, with longer durations per session, resulted in less improvement in working memory compared to more frequent sessions with shorter durations. This finding is supported by other studies evaluating the dose-response relationship of non-pharmacological approaches53.

Our review found that most studies indicated that follow-up assessments yielded similar results to post-test assessments. This finding is consistent with other studies, even those with follow-up periods of up to five years54-55. These studies suggest that in older adults with MCI, cognitive interventions provide long-term benefits by mitigating memory decline and slowing the progression of clinical symptoms; however, no effects were found on strategy use or activities of daily living54. Therefore, we suggest that while non-pharmacological interventions may improve cognition, they are not sufficient for enhancing the overall quality of life for MCI patients. Future research should focus on translating cognitive improvements into better daily living outcomes.

The findings of the meta-analysis section, along with previous studies, indicate that CIs, as a non-pharmacological approach, have a significant impact on improving WM; however, the effect size suggests a medium impact. Nevertheless, as noted earlier, the results of the meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution. Even so, we can conclude that non-pharmacological approaches still have the potential for improving working memory, as measured by the backward digit span test, which is the most commonly-used test to assess WM in MCI. Although our findings suggest that non-pharmacological interventions can be effective, further evaluation is needed to determine their effectiveness both independently and in conjunction with pharmacological treatments. In this regard, it has been shown that combining multiple approaches may yield beneficial results56.

Our findings can be useful for specialists implementing various interventions to rehabilitate individuals with MCI. In addition, rehabilitation medicine specialists should place greater emphasis on non-pharmacological approaches for MCI and carefully consider the parameters that may influence their effectiveness (e.g., assessments, intervention domains, session duration, follow-up, and frequency of weekly sessions).

Future studies should attempt to determine the optimal duration, intensity, and content of these intervention programs, as well as their potential long-term effects. It is also important to understand how participant characteristics, such as age, baseline mental status, and comorbidities, influence outcomes. Investigating the synergistic effects of integrating various interventions could lead to more robust improvements in cognition for older individuals with MCI.

CONCLUSIONS

Mild cognitive impairment represents a critical stage in cognitive decline, often preceding more severe conditions such as dementia. Our meta-analysis highlights the effectiveness of CIs in improving WM among older adults with MCI. The results demonstrate that CIs have a substantial impact on WM improvement, and that they offer potential as a valuable tool for enhancing cognitive skills in this population; as such, CIs are promising treatment modalities that can effectively address cognitive decline in individuals with MCI.